Things have changed a lot over the past ten thousand years or so. Nowadays we can travel from point A to point B by simply opening an app on our phone and following directions. “Continue straight for five miles. Turn left at the next intersection.”

Twenty years ago, the technology was still in its infancy and thirty years ago it was just a twinkle in Steve Jobs’ eye. You had to navigate your way with the aid of a paper map. It took time and it took planning and you had to know what you were doing.

There were days when you’d go out for a drive and just explore, just to discover previously unseen sights, but how many of us do that anymore? It’s the same with the stars.

Today we have computerised telescopes and apps that tell us where we should look. We don’t need those paper star charts, right? They’re a relic of bygone days that, like the road atlas you used to carry in your car, are simply a reminder of a time when getting lost was easy and finding your way was hard.

Imagine that no such maps or apps exist. Imagine trying to get from point A to point B by simply heading in the right general direction, somewhere “over there.” Imagine trying to find the Whirlpool Galaxy when you only know that it’s in the constellation of Canes Venatici.

Who Created the Earliest Star Charts?

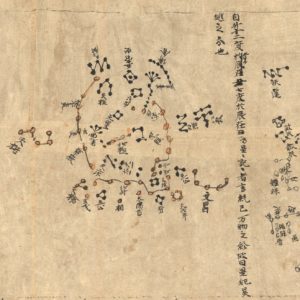

Our ancestors, of course, had no choice. They didn’t have the luxury of smartphones and apps. Instead, they typically recorded their observations of the stars on cave walls.

The earliest depictions of the stars date back tens of thousands of years and typically show constellations like Orion, Taurus or the night sky’s most famous star cluster, the Pleiades. In fact, back then, the constellations as we know them today didn’t even exist. They were simply groups of stars in the sky that people wanted to record for posterity.

The oldest civilizations – the Egyptians, the Mesopotamians, the Greeks – all had star charts depicting the night sky filled with their constellations. No longer designed to simply record the stars as they saw them, these charts allowed others to see them too.

Over the course of time, as trade and travel opened up previously unexplored areas of the world, the original 48 Greek constellations became adopted internationally. There was just one problem: the further south you went, the less those star charts and constellations were relevant.

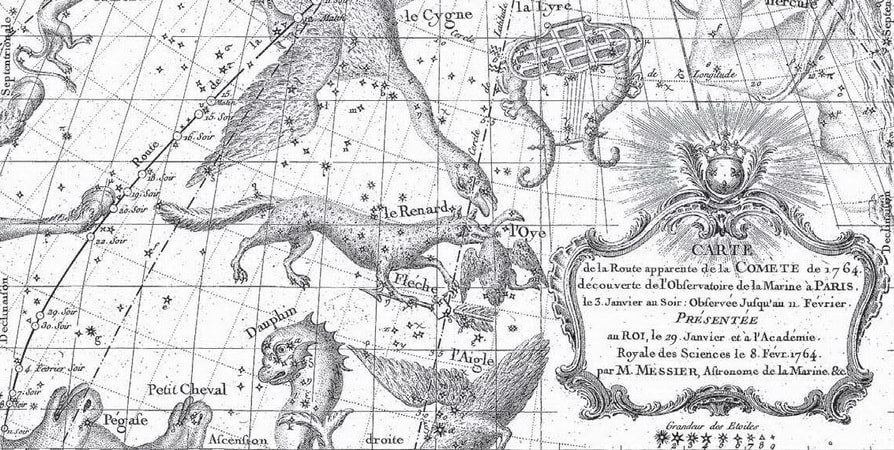

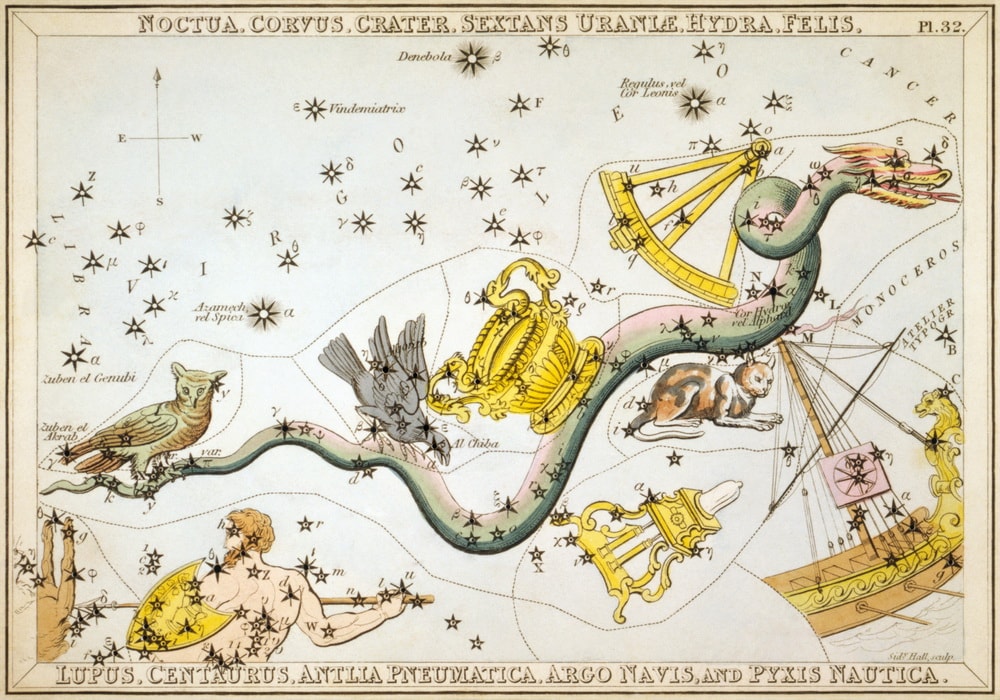

As the curve of the Earth took explorers to new lands, those same explorers found themselves under new skies, with strange stars and no identifiable constellations. Just as the ancient Greeks created constellations of creatures and characters familiar to them, so the astronomers of 17th and 18th century Europe added new, contemporary constellations.

Forty new constellations – such as the sextant, the compasses and, appropriately, the telescope – now became celestial companions to the original forty-eight. None of those were officially defined until 1922 when the International Astronomical Union determined the final list of 88 recognized constellations.

Until that time, many star charts had been produced depicting constellations that have since simply ceased to exist. For example, Noctua (the Owl), Aranea (the long-legged spider), Felis (the cat) and Hirudo (the leech), never gained enough popularity to survive.

All these charts helped observers to find and identify the stars and, until the invention of the telescope, they served their purpose. The telescope allowed astronomers to see thousands of deep sky sights that were simply invisible to the naked eye.

What is Right Ascension and Declination?

Cartographers could, of course, mark the positions of these objects on the star charts too, but there needed to be some way of recording those positions accurately and with no ambiguity.

Astronomy needed a coordinate system. Hence, the development of right ascension and declination.

If you’re familiar with the concept of latitude and longitude, then understanding the right ascension and declination shouldn’t be a problem for you. On maps and globes of the world, we use latitude and longitude to specify an object’s location upon the Earth.

While both are measured in degrees, latitude represents how far north or south of the equator the object is. Longitude then, measures how far east or west the object is, as measured from the Greenwich Meridian line in London.

The astronomers of the 18th century adapted this system to pinpoint the positions of the stars and deep sky objects. Instead of latitude, they used declination. Like its terrestrial equivalent, declination is measured in degrees, minutes and seconds and represents how far north or south of the celestial equator an object is.

Right ascension, the celestial complement to longitude, is a little different. Measured in hours (from zero to twenty-four), minutes and seconds, it denotes an object’s position from the point where the Sun moves north across the celestial equator in March.

(That point has a right ascension of 0 hours, 0 minutes and 0 seconds. Similarly, it has a declination of precisely zero degrees. It gets a little more complicated in that the point moves over the course of thousands of years, but that’s a topic for another time!)

For example, Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, has a right ascension (R.A.) of 6 hours, 45 minutes and 9 seconds. Its declination is -16 degrees, 42 minutes and 58 seconds. Its negative declination places it in the southern celestial hemisphere.

Incidentally, if you want to know if an object is (theoretically) visible from your location, there’s an easy way to figure this out. Simply deducting the absolute value of the declination from 90 will tell you how far north or south that object is visible.

For example, we know Sirius lies in the southern half of the celestial sphere because it has a declination of -16 degrees. If we take that absolute value (16) and deduct that from 90, we get 74. So Sirius may be visible from anywhere in Earth’s southern hemisphere, but it will never rise above the horizon for observers north of 74 degrees north. You will never see Sirius from the north pole!

Similarly, the bright star Arcturus has a declination of +19 degrees, 10 minutes and 57 seconds. This means it lies in the northern half of the celestial sphere. If we deduct 19 from 90, we get 71 – so the star will never rise above the horizon for observers south of 71 degrees south on Earth. That star will never be seen from Antarctica.

It might sound a little complicated at first but it’s relatively straightforward in practice. Having said that, you might be tempted to simply use a GoTo telescope instead. These computerised scopes have the coordinates of thousands of objects stored within them. By telling the scope which objects to look at, its computer looks up the coordinates and points the telescope in the right direction.

Easy, but where’s the fun in that? It’s far more satisfying to hunt your target and find it by star hopping – which we’ll come to shortly. If you find the idea of coordinates daunting, it might be wise to familiarise yourself with a star chart that’s a little easier to use.

Planispheres – The Night Sky at a Glance

Flip through almost any astronomy magazine and there, in the center pages, you’re sure to find a chart of the entire night sky. Since these magazines are typically published monthly, it’ll show you which stars and constellations are visible that month. It’ll also have a key on the same page telling you when to go outside and use the chart.

What you have is called a planisphere and it’s the ideal way to learn the night sky. By going outside and turning the magazine toward the appropriate horizon, you can get a good idea of what’s visible that night. For example, if the magazine says the chart is good for the 15th at 9 pm, you can go outside at that time and then turn the magazine so that whichever direction you’re facing is at the bottom.

Unfortunately, magazines can’t provide accurate depictions of the night sky for every location in the world. That, of course, would be simply impractical. They’re typically designed for the locale of their largest readership. Astronomy and Sky & Telescope magazines have charts for North American observers while The Sky At Night magazine has charts for those in the United Kingdom.

The good news is that they’re good enough to be used in most major towns and cities in that part of the world – and many are now printing equivalent charts for the southern hemisphere too.