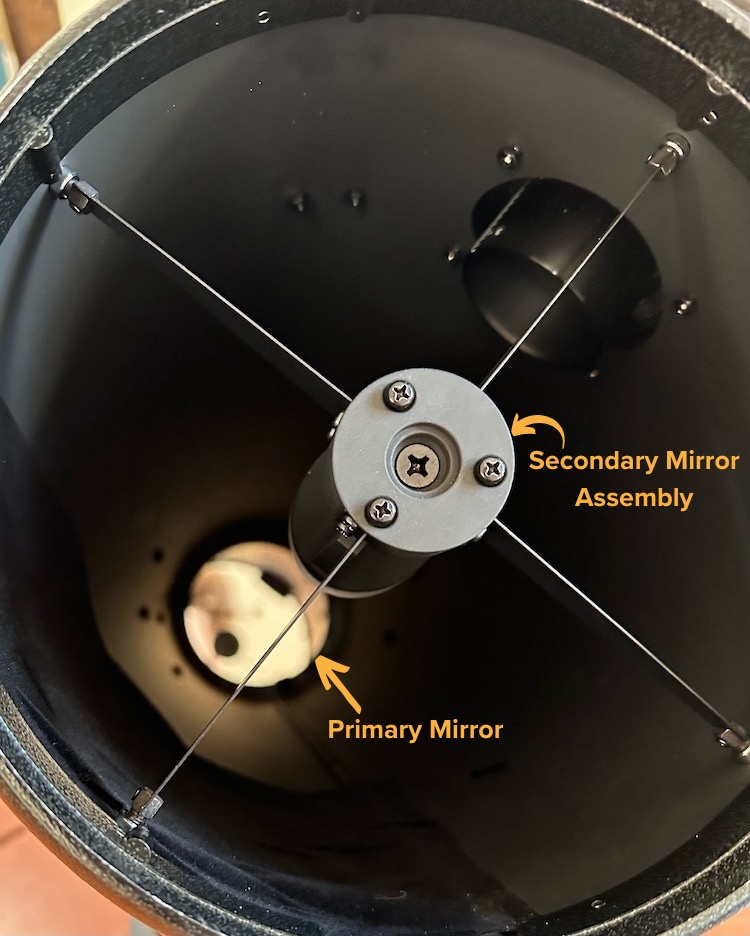

Overview of AD8 Optical Tube

The Apertura AD8 Dobsonian telescope uses a standard BK7 or soda-lime plate glass as its primary mirror material. With extreme temperature differences (for instance, bringing the scope outdoors on a freezing night), the primary mirror may take over half an hour to cool down, and thus a small battery-powered fan is installed on the back of the scope to speed up that process.

The mirror is easy to collimate, but I’d recommend removing the “mirror lock” bolts from the back of the mirror cell. They are supposedly there to help the telescope retain collimation better during transport. But in practice, all they really do is make collimation more confusing. And if the telescope is dropped, it may slam into the mirror and crack it.

The plastic front cap included with the Apertura AD8 Dob tends to not fit very tightly, and if it does, it may become difficult to remove. What I usually do is attach some kind of handle to it and line the edges with tape for a snug fit.

The AD8’s tube is about 2” (5 cm) longer than the Synta-made 8″ Dobsonians sold by Sky-Watcher, Orion, and others. As such, it may not fit in the trunk or boot of some smaller vehicles and must be laid across the back seat.

The focuser on the AD8 is a well-made GSO dual-speed Crayford. The “dual-speed” aspect is a small 1:10 reduction knob on one side that allows for extremely fine focusing, down to just a few microns of adjustment. This has always been helpful at high magnification. The focuser uses a brass compression ring to grab your eyepieces and comes with a 1.25” adaptor with its own compression ring as well.

Accessories With The Apertura AD8

The Apertura AD8 Dobsonian includes a 9x50mm right-angle correct-image finder scope, a laser collimator, a “Moon filter,” and two eyepieces: a 2”, 30mm “SuperView” (40x) and a 1.25” 9mm Plossl (133x). At the price that the telescope is being offered, the package simply cannot be beat.

A Working Finderscope

The Apertura AD8’s included 9×50 finderscope works. But on its own, it can be mildly frustrating to use to aim the telescope. I have to sight along the telescope’s optical tube, then look into the finderscope to actually center the telescope on my target. This can be a bit confusing if you’re not familiar with the sky.

Brighter deep-sky objects like the Andromeda Galaxy can be easily seen in the finder under light-polluted skies that make them invisible to the naked eye, along with stars down to 9th magnitude. But the confusion of using the 9×50 somewhat offsets these gains for beginners.

A zero-power red dot or reflex sight is easier to use and can complement or replace the 9×50 finder.

The Lacklustre Laser Collimator

The AD8 Dobsonian comes with a laser collimator that is supposed to make collimation easy.

However, for one thing, the laser itself is frequently out of square with the barrel when it arrives. This then requires adjustments with a hex key and has to be placed in some sort of makeshift V-block to confirm that it is parallel, which may be a bit of a headache for a lot of beginners. Without this work, the laser is little more than a decoration.

Seating the laser collimator properly and squarely in the focuser is also very important. Otherwise, the laser may look dead on when your collimation is, in fact, quite far from correct.

The Greatly Complementing Eyepieces

The included 30mm SuperView is a great low-power eyepiece.

You might notice that the stars near the edges aren’t as clear. This is because of the coma, which is a feature of any Newtonian telescope with an aperture of f/6 or faster, and astigmatism at the edge of the field with the eyepiece. You could buy nicer eyepieces that have sharper stars and wider fields of view, and a coma corrector to eliminate the coma. But at that point, you’d be spending nearly as much as the whole scope costs.

Compared to the standard 25mm Plossl supplied with most other beginner scopes, the 30mm SuperView is a joy to use and is a great eyepiece for both general viewing of deep-sky objects as well as finding them.

The included 9mm Plossl is rather short on eye relief. This means you have to press your eye quite close to it to get the full view. However, it’s quite sharp, and 133x is enough for some nice views of the planets. Overall, the 9mm Plossl is a nice little addition.

The Unnecessary Moon Filter

I’d classify the included 1.25” “Moon filter” as complete junk. It’s a piece of tinted green glass that dims the view at the expense of sharpness and turns everything green. It’s basically worthless.

The Almost Perfect Dobsonian Mount

For azimuth (side-to-side) movement, the Apertura/GSO Dobsonians use roller bearings, which are essentially a “lazy Susan.” This is different from most Dobsonians, which use Teflon pads and laminate arrangements. This approach works fine, but it can be a bit hard to get the right amount of motion—a lot of people tend to complain that the scope is too stiff or spins too freely, which can make aiming and tracking with the telescope at high magnification a bit frustrating. The scope is also prone to easily spinning around if it’s windy.

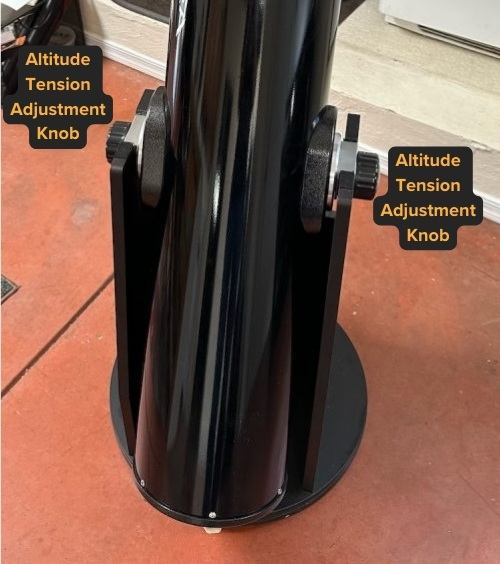

The Apertura AD8’s altitude (up/down) bearings are ball bearings that can be adjusted back and forth along the tube to compensate for the telescope’s changing center of gravity, depending on what eyepieces/finders/etc. you prefer using. This can’t easily be done in the field, but it suffices for balancing with most stuff. You can also adjust the friction by tightening two large knobs on the bearings.

Like most mass-manufactured Dobsonian telescopes, the AD8’s mount is made out of melamine-covered particleboard and can be assembled in a few minutes with the included hex key.

Should I buy a used Apertura AD8?

A used Apertura AD8 Dobsonian is a wonderful scope. Make sure that the mirrors are reflective and you can’t see through them. Some dirt/grime is fine and can probably be cleaned, but coating damage means you’ll need the mirrors recoated, which easily negates any cost savings from buying used.

A damaged base isn’t a show-stopper, however; making a new one out of plywood is relatively inexpensive and easy to do (and a plywood base actually weighs less than the original anyway).

Alternative Recommendations

The Apertura AD8 Dobsonian telescope is easily the best telescope in its price range, but if you must consider alternatives, here are a few we’ve selected:

Under £600

- The Explore Scientific 10” Hybrid Dobsonian offers even more aperture for the money than the AD8, and in a collapsable truss tube package. However, the included accessories are not very good, the focuser is only a single-speed design, and some modifications are required to make the telescope perform well, not to mention to put the eyepiece at a comfortable angle.

- The Sky-Watcher Virtuoso GTi 150P has less aperture than the AD8, but is ultra-portable and features full motorised GoTo and tracking. You can pick it up with one hand and be observing in minutes. The manual Heritage 150P offers the same features minus the GoTo.

- The Orion SkyQuest XT8 has fewer features or included accessories than the AD8, with just one eyepiece, a red dot finder, and a single-speed 2” Crayford focuser, though the price is slightly lower and the design of the altitude bearings is arguably superior compared to the AD8.

£600-£800

- The Apertura AD10/Zhumell Z10/Orion SkyLine 10 is essentially a scaled-up AD8 with identical features, quality, and portability but with almost double the light-gathering ability and a minimal increase in weight, bulk, and price.

- The Celestron StarSense Explorer 8” Dobsonian is similarly minimalist to the XT8 in terms of features and accessories – besides of course including Celestron’s StarSense Explorer phone dock and technology to make aiming at targets in the night sky easier.

- The Sky-Watcher 8” FlexTube Dobsonian doesn’t have the best bearing design or accessories, but its collapsable tube can save you some space in storage or transport if this is an absolutely critical factor.

What can you see with Apertura AD8?

The AD8 can show you a lot of things. Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s cloud belts are easy to spot, as are their moons. Saturn’s cloud belts, the Cassini division in the rings, and Jupiter’s Great Red Spot are a bit harder. On a steady and clear night, you’ll be able to see Jupiter’s moons as tiny disks with their shadows following them as they transit across the planet, an event that happens almost every night. Mars’ dark spots and ice caps can be seen when the Red Planet is near Earth for a handful of months every two years, and with certain observing tricks, you might even be able to spot its tiny outer moon, Deimos. Venus and Mercury are devoid of detail—the former is covered in clouds, and the latter is tiny, never high in the sky, and lacks large, high-contrast features—but you’ll be able to see their phases easily. Uranus and Neptune are bluish dots, their moons on the limit of visibility with dark skies. At magnitude 13, Triton, the moon of Neptune, is the brightest and easiest to find. At magnitude 14, Oberon and Titania, which orbit Uranus, are the next brightest and easiest to find. With some effort, Ariel is also visible around Uranus, although it’s a bit harder to see than Oberon and Titania. Under dark skies, the Apertura AD8 can just barely see Pluto as a point that looks like a star. However, for the next few decades, Pluto will be surrounded by thousands of stars with the same brightness, making it hard to find.

Outside the Solar System is where the AD8’s aperture becomes even more helpful, though keep in mind that the quality of your skies (i.e., how dark they are) is extremely important when it comes to viewing “faint fuzzies”. Under dark skies with the Apertura AD8 dobsonian telescope, you can see details such as spiral arms, dark dust lanes, and nebulae (known as H-II regions) in spiral and irregular galaxies like M31, M51, M33, M82, M82, and many of the galaxies in the huge Virgo Cluster. Emission nebulae like Orion, the Lagoon, and the Swan look fantastic. With an aftermarket UHC or Oxygen-III filter, you’ll be able to see the Veil Nebula, which stretches across an area of sky several times the width of the full Moon. Planetary nebulae like the Ring and Cat’s Eye are bluish or greenish with lots of small details, and you’ll have no trouble resolving globular clusters into individual stars, even with fairly light-polluted skies. Open star clusters like the Double Cluster look magnificent and colourful no matter where you are.

Keep in mind that without dark skies, many galaxies lose their details or disappear from view entirely, while nebulae become shadows of their former splendid selves and globular clusters lack sparkle and contrast. Thankfully, the AD8 is pretty portable and thus easy to transport to a good viewing location. Additionally, a properly cooled and collimated instrument, along with steady skies, are needed to get the best views of the planets, the Moon, and other small targets—the first two factors you can control, while the third depends on general location and luck.