Overview Of The 127mm Bird-Jones Optical Tube

Once we do some basic math, we’ll immediately notice something odd with the specifications of the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ. The optical tube is only twenty inches (500 mm) long in reality. How does one fit a “Newtonian” optical system with a 1000mm focal ratio (not a Cassegrain optical system, which actually “folds” the light path into a smaller physical package) into that small of a tube?

The answer is that the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ is not a Newtonian. It’s a Bird-Jones.

The Main Villain: Bird-Jones Optical Design

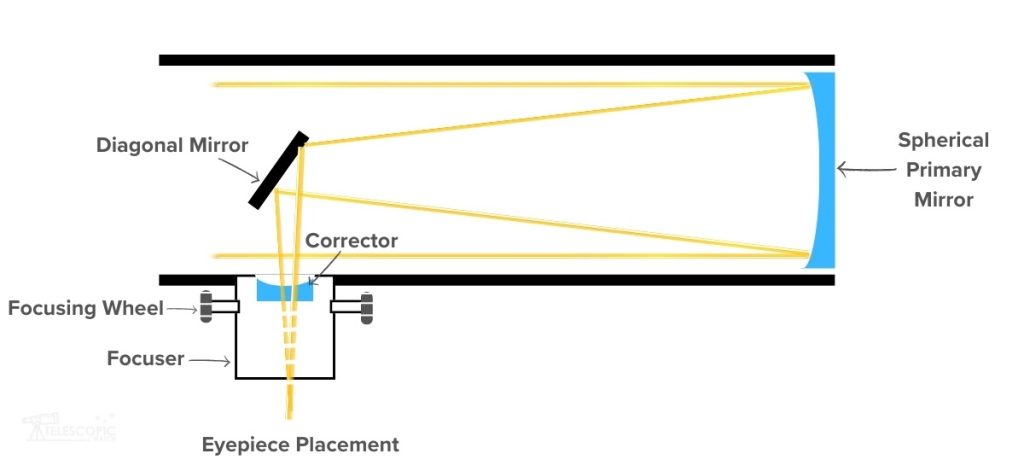

Bird and Jones were two amateurs in the 1950s who sought to create a simple telescope with a spherical instead of a parabolic primary mirror and a corrector lens/Barlow in front of the secondary/diagonal mirror. This design, in theory, can work well, and some properly executed Bird-Joneses do, in fact, work quite well.

But the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ is anything but properly executed.

Unlike the classical Bird-Jones style, which puts the corrector lens just in front of the secondary mirror, the 127EQ’s “corrector” is mounted in the focuser (see the picture below). This means that the corrector will move whenever we move the focuser, thus assuring the correction is basically never spot-on.

Even if the corrector’s placement was not an issue, the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ’s corrector itself is not a proper corrector lens. It is just a Barlow lens inserted into the focuser drawtube. So, it doesn’t fix the problem it’s supposed to fix as per the theory: the spherical aberration caused by the use of an f/3.5 spherical primary mirror in the 127EQ. This spherical aberration makes it impossible for the telescope to make sharp images, even at very low magnifications.

Rather, the corrector-Barlow simply makes the path of the light rays through the telescope a little steeper, which in theory might be enough to provide a pretty decent, if not the sharpest, image. But because it is mounted in the focuser, the 127EQ’s corrector is always moved away from its ideal position. This means that the scope can only produce images that are barely good enough for a telescope of its size and price. At worst, the views are a completely mushy, unusable mess.

Next Problem: Improperly Made Primary Mirror

To make matters worse, the PowerSeeker 127EQ’s primary mirror isn’t even a precisely manufactured sphere. It’s a random shape that came straight out of the polishing machine.

The PowerSeeker 127EQ primary mirrors that I’ve tested have had rough surfaces and all sorts of microscopic holes and hills that damage the image, as well as many other complicated flaws.

These are all caused by the fact that nobody actually bothers to test these things before throwing them in the telescope. If Celestron had performed any quality control on the PowerSeeker 127EQ, after all, it might not have been created in the first place.

The primary mirror also appears to me to be secured to its support with solid gobs of epoxy, which warp and distort the mirror due to the stress they induce on the glass. I believe this further hinders the already limited capabilities of the telescope.

The Difficulties in Collimating the Scope

With the corrector lens in the focuser, it’s hard to collimate the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ because the corrector makes the reflected images of the primary and secondary mirrors look very small. The corrector lens also inhibits the function of a laser collimator.

So, to collimate the 127EQ, I must first remove the corrector lens. This means taking apart the focuser, carefully unscrewing the ring that holds the corrector, and being careful not to get fingerprints or grease from the focuser drawtube on the corrector lens. I then temporarily put the focuser back together to collimate.

After collimating the scope, I then have to take the focuser apart again, re-install the corrector, making sure to put it in the right way, and then re-assemble the focuser.

The Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ also has collimation screws that don’t move much and are easy to strip.

Collimating the 127EQ was hard enough for me to do in the shop; a beginner attempting it out in the cold and dark will find it impossible.

Problems With Celestron Powerseeker 127EQ Accessories

If you thought the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ’s optics were bad, the eyepieces are actually worse by every stretch of the imagination.

The 50x low-power eyepiece that comes with the 127EQ is a 20mm Kellner. 50x is a bit of a high magnification for “low power” with a 5” telescope, especially one with poor optics.

The 20mm Kellner has a permanently installed “erecting prism” that flips the image right-side up. The erecting prism is included so that Celestron can claim that the telescope is capable of terrestrial viewing. But it comes at the expense of sucking up quite a bit of the light entering the telescope, blurring the image due to its extremely low quality, and providing a field of view reminiscent of a drinking straw. Because of this, it will be hard to find targets or fit them into the field of view. The included next-to-useless finderscope won’t help much with this.

For high magnification, the 127EQ comes with a 4 mm Ramsden. The last time a Ramsden had any place in an amateur astronomer’s eyepiece box was in the 1960s, when a Kellner or Orthoscopic was rare and sought after.

Like the included 20mm eyepiece, the 4mm Ramsden has a tiny field of view. Worse, however, it has a tiny eye lens and next to no eye relief—meaning I’ve got to jam my eyeball into it to see much of anything. And it provides 250x, which is too much for even a quality 5” telescope (which the 127EQ is a far cry from). It’s also generally low quality and would provide a mushy image anyway, even if there were not too much power for the scope to handle.

The included “3x Barlow” is a plastic-lensed abomination that exists to provide the “450x” Celestron claims the telescope is capable of (in actuality, very few telescopes are capable of, let alone used at, 450x). It is completely useless and should be discarded.

For a finderscope, the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ comes with a 5×24 unit with a single plastic lens and a plastic eyepiece. To get a usable image, the lens’s aperture is closed down to less than 10 mm. This takes away its ability to gather light. The bracket is also hard to align with the telescope, so the finder is almost always pointed in the wrong direction and is therefore useless. You’re better off removing the finder itself and using the bracket as a peep sight.

The Undersized EQ-1 Mount

The EQ-1 mount provided with the PowerSeeker EQ telescopes is actually fairly respectable in terms of build quality and operation. But it can’t hold up a telescope as big as the PowerSeeker 127.

Not only is the mount very unstable when the 127mm optical tube is on top of it, but the counterweight that comes with the telescope is not heavy enough to keep it balanced. So, when using the 127EQ, I always have to lock up the mount axes a little bit to keep the whole telescope from moving around on its own. This means that as I move the telescope around the sky, the motion is jerky and less than smooth, which makes the stability problems I’ve already talked about even worse.

Between these issues and the terrible included finderscope, it is hard for me to get the 127EQ pointed at pretty much anything besides the Moon.

Should I buy a Used PowerSeeker 127EQ?

No, not even for £1.

Alternative Recommendations

Almost anything is going to be better than the PowerSeeker 127EQ; even a pair of 7×50 binoculars is likely to lead to more satisfaction in exploring the night sky. However, here are a few of our top picks:

Under £250

- The Zhumell Z100 and Sky-Watcher Heritage 100P have less aperture than the 127EQ, but thanks to the ridiculously poor design of the 127EQ they of course easily best it in image quality. These telescopes – as with all others we recommend both feature parabolic primary mirrors with no internal corrector lenses, and quality accessories and mounts.

- The Zhumell Z114 and Orion StarBlast 4.5 Astro are both even better than the smaller 100mm tabletop scopes we also recommend, with the same great optics, accessories, and easy-to-use mounts. They are night and day compared to the awful experience of the 127EQ.

- The Sky-Watcher Heritage 130P offers slightly more aperture – and infinitely better views – than the PowerSeeker 127EQ, all in a convenient and portable package thanks to its collapsable tube. The included accessories are great, too.

£250-£325

- The Sky-Watcher Heritage 150P offers significantly more aperture than the 127EQ or smaller tabletop reflectors we recommend in its stead, with a surprisingly compact tube thanks to Sky-Watcher’s FlexTube collapsable tube design. A computerised version, the Virtuoso GTi 150P, is also available at a slightly higher price but still offers the freedom to be aimed manually if you wish.

- The Bresser Messier 6” f/8 Planetary Dobsonian provides similar performance to the Heritage 150P, but with a solid-tubed design and a tube and base tall enough to not need a table. It’s a lot more rugged than a tabletop scope, but also a lot more of a hassle to move around. The similar Apertura DT6 and Sky-Watcher 6” Classic are also great choices, but the XT6 is our favourite of the three thanks to its features, price, and availability.

Aftermarket Accessory Recommendations

It might be perceived as an unwise investment to upgrade the PowerSeeker 127EQ with better-quality eyepieces when the funds could be allocated towards simply obtaining a more effective and capable device. Nevertheless, replacement, good quality 1.25” eyepieces can be employed with a different telescope in the future and can mildly improve the viewing experience with your PowerSeeker 127EQ, in spite of its flawed optics, terrible finderscope, and unsteady mount. The 127EQ’s provided 20mm erecting eyepiece is awful and completely spoils any low-power viewing, where the telescope can still do a mediocre but admittedly acceptable job. A good low-power eyepiece gives you a fighting chance. Our pick would be a 32mm Plossl (31x), which is far sharper than the 20mm and presents the widest feasible field of view with the scope, making it ideal for examining deep-sky objects and able to put up decent images of the Moon too. However, it will vignette slightly thanks to the corrector lens in the 127EQ’s drawtube, though it is still a better option than a 25mm unit. A 15mm “redline” or “goldline” eyepiece (67x) should still be capable of providing sharp images in the 127EQ and can unveil some planetary detail without surpassing the limits of what the telescope can genuinely manage before the optics yield indistinct and faint images.

A higher magnification eyepiece such as a 9mm goldline/redline (111x) will be great with another telescope but is probably going to be a disappointment in the 127EQ – though it’s certainly far better than the absurd 250x with the provided toylike 4mm Ramsden eyepiece.

What can you see with the Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ?

The Celestron PowerSeeker 127EQ’s low-quality optics are a permanent handicap, even if you upgrade the accessories. If you can manage to get the scope collimated and deal with the frustration of aiming it, expect to see the following.

Solar System

- Mercury – An ill-defined smudge. It’s unlikely you’ll be able to resolve its phase.

- Venus – The phase is easy to see, albeit with a lot of glare surrounding the planet caused by the corrector lens and low-quality eyepieces.

- The Moon – A fairly decent view, but nowhere near as detailed as the sights delivered by a telescope with quality optics.

- Mars – An ill-defined blob even when it’s close to Earth. You might just be able to make out an ice cap and maybe a dark smudge.

- Jupiter – The moons are obvious (but then again, they’re obvious in a pair of cheap birding binoculars too). The two equatorial cloud belts are visible, albeit low in contrast. The Great Red Spot, normally a pretty easy catch with a careful eye and almost any half-decent telescope, is not sharply defined enough to spot.

- Saturn – The rings are visible, though fuzzy, and maybe a couple of moons can be spotted. The Cassini Division in the rings cannot be seen, and you won’t be able to glimpse any of Saturn’s fainter moons besides Titan and Rhea.

- Uranus and Neptune – Assuming you can even find them, the PowerSeeker’s optics are bad enough that you can’t distinguish either planet as a clear disk.

Deep-sky objects

Many of the most exciting star clusters are visible, but lack crispness.

- Emission nebulae: The Orion Nebula looks okay but the Trapezium star cluster is mushy. The Lagoon is a wispy cloud, with bloated, ugly stars inside it. The Swan is ill-defined.

- Galaxies are troublesome to find and lack anything resembling detail.

- Forget most planetary nebulae; they’ll be blurred beyond recognition.

- Splitting any remotely close double star with the 127EQ is impossible.