Optical Tube Assembly of AstroMaster 114EQ

The Celestron AstroMaster 114EQ is supposedly a 114-mm-aperture Newtonian reflector with a focal length of 1,000 mm. This focal length specification itself should immediately raise some eyebrows, as the length of the optical tube of the telescope (measures 395mm) is obviously way too short to accommodate such a focal length. Typically, the focal length of Newtonians are somewhat close to the actual tube length of the telescope.

So, what’s going on?

Well, the AstroMaster 114EQ isn’t actually a Newtonian. It’s a Bird-Jones (or Jones-Bird, depending on who you ask).

Bird-Jones Design: Why I Don’t Like It?

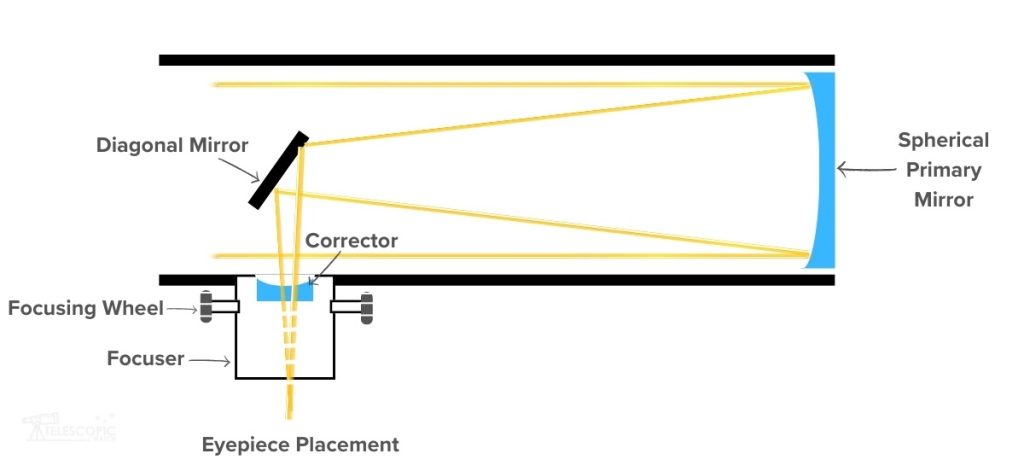

As originally designed by Bird and Jones, this telescope optical design uses a spherical primary mirror (unlike a true Newtonian that uses parabolic primary mirror) with a corrector lens just before the secondary mirror. True Newtonian design doesn’t make use of a corrector lens at all.

This Bird-Jones design allows for the secondary mirror to be shrunk down, and the primary mirror can take the shape of a sphere that is easy and cheap to make. The introduction of the corrector lens in the Bird-Jones design also results in a long focal ratio telescope that is stout and stubby with next to no coma.

At the time the Bird-Jones was designed, eyepieces were simple and coma correctors were nonexistent. So in order to achieve sharp images, focal ratios had to be on the long side.

But today, even the cheap Kellner eyepieces supplied with many entry-level telescopes work well enough with a relatively short focal ratio telescope. They would’ve amazed a 1950s amateur with their quality.

So today, the Bird-Jones design is outdated and no longer needed.

Furthermore, Celestron didn’t even bother to execute the Bird-Jones design correctly.

Celestron’s Bird-Jones design places the corrector lens inside the focuser, as shown in the above picture. This causes two problems.

- It means that the spacing between the corrector and the primary mirror is not fixed unlike the original Bird-Jones design. Instead, the spacing varies when focuser is racked in/out depending on what eyepiece you’re using and also whether you’re nearsighted or farsighted. Thus, the corrector lens’ purpose isn’t always being fulfilled correctly.

- The corrector can’t easily be removed, which is required to precisely collimate the telescope. Perfect collimation is a necessity to achieve sharp images.

The problems don’t end here, though.

The correctors in these scopes are incredibly cheaply made and aren’t remotely close to the right shape. These are glorified cheap Barlow lenses. As a result, the 114EQ cannot achieve decent images even when well-collimated, which itself is hard to do as I stated before.

The Problem of Plastic Castings

Moving on to the mechanical aspects of the OTA, we come to another problem: the plastic castings.

The giant casting with the AstroMaster logo that protrudes nearly halfway along the tube, as well as the area around the focuser. This means that I cannot slide the tube in its rings to achieve balance on the declination axis in most situations. This strains the mount and is a nuisance while observing, as I will always have to tighten the declination axis.

Problems In Other OTA Design Features

The focuser on the Celestron AstroMaster 114EQ is a modest and functional 1.25” rack-and-pinion, mostly made of plastic, apart from the knobs.

The finderscope is a standard StarPointer red-dot finder. Though until recently, most AstroMaster scopes I’ve had my hands on had an obnoxious and often-faulty built-in red-dot finder.

The Celestron AstroMaster 114EQ comes with standard tube rings and a very short Vixen dovetail, which would allow us to put the scope on a different mount, if we want to. But I see it as the equivalent of putting premium dipping sauce on McNuggets—the prime ingredient is still cheap and the secondary ingredient is never going to compensate for that.

One of the rings has a captive ¼ 20 knob, so I can piggyback a DSLR camera on top. But this often further wreck the balance, and is too much for the mount to handle.

The Bad Eyepieces Experience

The AstroMaster “Newtonians” all come with a 20 mm “erecting” eyepiece for low power magnification, just like in the case of the infamous Celestron PowerSeekers series.

The 20mm eyepiece is almost entirely plastic, has a narrow field of view, and isn’t sharp in the slightest. Celestron includes this eyepiece solely so they can sell it at nature and science stores under the premise of it being capable of terrestrial viewing.

The other eyepiece included with all AstroMaster telescopes is a 10 mm Kellner. It works fine in most other telescopes I’ve used the same eyepiece with. But the AstroMaster 114EQ is, of course, incapable of delivering a sharp image with it.

The CG3 Mount

The mount Celestron supplies with the AstroMaster EQ telescope is known as the CG-3, though some literature refers to it as a CG-2. Celestron’s CG numbering system is confusing to me. I’m of the opinion that they should ditch it and stick with the EQ1-8 system that other companies use.

The CG-3/CG-2 is of the run-of-the-mill, cheap, and German equatorial design, with tiny, useless setting circles that are little more than decoration. It has 1.25” tubular steel legs and lots of plastic castings on the tripod.

The CG-3 has flexible slow-motion cables for both axes, fine adjustments in altitude, and an azimuth for accurate polar alignment. You can also equip the mount with Celestron’s logic drive for hands-free tracking.

The Balancing Problem

German equatorial mounts can often place the eyepiece of a Newtonian in an awkward position, and we must rotate the tube in its rings to reposition it somewhere more comfortable. Normally, when doing this I’d have to worry about accidentally sliding the tube forward or backward when the rings are loosened, and thus possibly ruining the declination axis balance. But since the optical tube can’t really slide far in either direction and the balance is so messed up anyway, I don’t consider this to be much of an issue to start with.

Were it not for the balance issues, the CG-3 would actually make a fairly adequate mount for the Celestron Astromaster 114EQ. However, given that the telescope cannot actually balance on the declination axis, it is nearly impossible to aim accurately.

lternative Recommendations

At the same price as the AstroMaster 114EQ, there are a lot of good scopes. A few we’ve selected include:

- The Zhumell Z130, with significantly more aperture, better optics, better accessories and an easy-to-use Dobsonian mount.

- The Sky-Watcher Heritage 130P, essentially the same telescope as the Z130 but with a collapsable tube.

- The Skywatcher Skyhawk 1145P Reflector Telescope offers everything the AstroMaster 114EQ promises but with significantly better optics and accessories.

- For a bit less money, the Zhumell Z114 offers a 114mm telescope like the AstroMaster or StarBlast but with great accessories, great optics and a simple, lightweight and affordable Dobsonian mount.

For additional options that might be right for you, check out our Telescope Rankings page

Aftermarket Accessory Recommendations

Upgrading the Celestron AstroMaster 114EQ with superior eyepieces might be seen as futile or outright expenditure when the money could be better spent on acquiring a more advanced and efficient instrument. However, you might as well try to get the best views out of this scope if you’re stuck with it. In any case, decent 1.25” eyepieces are transferable to another telescope in the future and can significantly enhance the observing experience with your 114EQ, despite its imperfect optics and wobbly mount. At the very least, you’ll want a passable low-power eyepiece. A quality 32mm Plossl (31x), while somewhat vignetted by the scope’s corrector lens, offers the widest achievable field of view with the scope and is perfect for observing deep-sky objects, where its optical flaws and vibrations won’t show up as much due to the low magnification. A 15mm “redline” or “goldline” eyepiece (67x) should still manage to deliver crisp images with the 114EQ and can expose some planetary detail without exceeding the telescope’s realistic capacity, beyond which the optics merely produce blurry and dim images. The provided 10mm eyepiece works well enough and pushes the 114EQ’s optics far enough that replacing it with a 9mm goldline or redline eyepiece is probably not worthwhile.

Astrophotography

The optics in the AstroMaster 114EQ are so bad that you can completely forget about taking decent pictures with it. Even if this were not the case, a camera, whether directly coupled or piggybacked, would ruin the balance and strain the CG-3 mount too much.

What can you see with the Celestron Astromaster 114EQ?

If we manage to get it collimated, the AstroMaster 114EQ can give us fairly nice views of the Moon.

- Venus’ phases can be seen, while Mercury’s is a little more difficult.

- A dark spot or two on Mars, along with an ice cap, is possible when the planet is close to Earth.

- Jupiter’s moons and cloud belts are easy, while the polar zones and Great Red Spot elude us.

- Saturn’s rings and a few moons can be spotted.

- Uranus and Neptune are fuzzy, star-like dots, assuming we manage to locate them in the first place.

Deep-sky objects are a little more forgiving, though the included 20mm eyepiece make it feel a bit claustrophobic when viewing them.

- Open star clusters like the Double Cluster are easy, while globular clusters are unresolvable fuzzy smudges.

- You might have difficulty distinguishing many of the smaller planetary nebulae from stars, though the Ring and Dumbbell are easy.

- Galaxies have detail-less smudges even from dark skies, apart from M82 and its dust lanes. A few emission nebulae like Orion and the Lagoon are mildly intriguing, if washed out easily by light pollution.