Care for, cleaning, and recoating telescope mirrors is a complicated and confusing subject.

All telescope primary and secondary mirrors, as well as star diagonals, are first-surface mirrors, which use an extremely thin reflective coating on their front surface (as opposed to a bathroom mirror, which has its coating on the back). This means that the reflective side is exposed to the air and all that comes with it—atmospheric chemicals, fingerprints, dust, dew, and so on.

Coatings all have a limited lifetime, depending on the type of coating and where we store our telescope.

Types of Mirror Coatings

There are essentially four types of coatings you’re likely to see on telescope mirror surfaces:

1. Aluminium Coatings

Standard aluminium coatings are by far the most common coatings on mirrors today.

Most of these mirrors have either standard aluminium or aluminium that has been slightly enhanced chemically. These coatings are just aluminium with a thin quartz overcoat deposited on top afterwards to protect it.

The coatings are deposited on the mirror in a vacuum chamber in one go, with typical reflectivity around 89-93%.

Standard aluminium coatings can probably last centuries if kept in good storage. I’ve even seen well-maintained telescopes from the 1940s-1950s, when aluminium coatings became common, which are still just as capable as a brand-new scope.

There are some who claim aluminium coatings lose reflectivity as some sort of innate property over time, which I think is incorrect. They only lose their reflectivity if they are damaged, either from poor handling, poor cleaning, or simple negligence and lack of maintenance.

A regular aluminium coating can be easily stripped with ferric chloride or “green river” solvent prior to recoating. The coating is generally durable enough that accidentally touching it or using a lens wipe to remove fingerprints probably won’t hurt it.

2. Enhanced Aluminium Coatings

Enhanced aluminium coatings, from what I’ve seen, are usually just like regular ones, but some can have multiple reflective/protective layers that make stripping and recoating them harder.

They can also attract certain contaminants more easily. “Beral” coatings, for instance, are usually far more sensitive to salty air.

On the flip side, many enhanced coatings offer reflectivity of 94-96%, and the extra layers can make them far more durable than a standard coating.

3. Dielectric Coatings

Dielectric coatings are more reflective than aluminium (often exceeding 95% in reflectivity) and are essentially permanent. They are composed of many layers that are essentially impossible to remove and difficult to damage.

However, they are extremely expensive and have issues with being used on larger mirrors. I’ve seen them on star diagonals, but that’s about it.

4. Silver Coatings

Silver coatings were common in the days before aluminising mirrors became common and affordable. Silvered mirrors—specifically spray-silvered ones—are enjoying a comeback as of late on large, cheap Dobsonian telescopes.

Silver coatings can last up to a year or two and enjoy 99% reflectivity.

But they tarnish easily and are extremely easy to damage. They have to be applied and reapplied by ourselves and generally aren’t worthwhile for smaller optics. As such, they are a bit of a speciality, and I won’t be discussing them further. (For those curious, more info on spray silvering can be found here.)

The rest of this article will focus on the care, maintenance, and recoating of aluminium and enhanced aluminium coatings. These far outnumber silver-coated mirrors, and as mentioned, dielectric mirrors are generally only found in star diagonals and are very easy to clean and take care of.

Taking Care of Mirror Coatings

The easiest way to preserve our mirror coating is to not let it corrode or get dirty in the first place.

- Solid-tube telescopes

If the telescope has a solid tube, I always keep the caps on it and make sure that it is kept in a clean and dry environment. Desiccant caps can be purchased to keep moisture out of your tube if you live in a place where the relative humidity is always high.

Mice, bugs, and large amounts of water are hard to get into a solid tube unless we’re very careless. A weatherproof cover to keep the telescope cool and dry is a good investment if you’re somewhere where the telescope might be set up for a few days, such as a star party.

- Truss-tube Telescopes

Truss tube Dobsonians’ optics are a little more exposed by default, and as such are more prone to getting dusty or invaded by critters.

I think it’s worth getting a cover to keep your lower tube assembly closed up when it’s stored. A tight-fitting cloth bag or plastic cover for our secondary mirror is more than adequate to protect it.

My Mirror Is Dirty—What Should I Do?

First—stop! If your mirror has a light layer of dust, there is nothing you should do. Dust is inevitable.

In small amounts, dust causes negligible additional scatter and light loss. Cleaning it off is more likely to leave more debris, fingerprints, and microscopic scratches that cause far more image quality loss than the dust itself. Most of the time, I’ve learnt that a “dusty” mirror is not worth messing with. Leave it alone.

If your mirror is covered with enough dust, dirt, or grime that it is noticeably dulled or smudged, don’t worry! Cleaning is a relatively simple and painless procedure. You should definitely clean your mirror if it gets lots of pollen or dew on it, or if any mouse or bug waste is on it.

How I Clean My Mirror

Keep in mind that the only time a coating will look perfect is the day it was made. You should be aiming for improvement, not perfection, when it comes to the cleanliness of your mirror.

And don’t use a flashlight as a gauge for how dirty your mirror is; your mirror will almost always look horrific under a bright enough light, but it will work just fine under the stars.

- Rinse Technique

I first remove the mirror from its cell to clean it. Some mirrors may be glued to part of the mirror cell, which is fine. I then just take the mirror and whatever it is glued to out and proceed. I’d leave the mirror glued to its support.

A rinse with tap water, followed by rubbing dish soap on and lightly swirling around with your finger, and then a final rinse with distilled or de-ionised water (to prevent spots) is all I need to do. I then blot the mirror with a clean paper towel (or even better, a microfibre cloth) to prevent spots and speed up drying. If you used distilled water, you can use a hairdryer to speed up the drying process.

Big Dobsonians with an open mirror box can have the mirror rinsed in situ with a spray bottle, provided you have some way to wipe up the water that drips onto the base.

If you’re still unsure of the process, here are a few videos on mirror cleaning I recommend watching (1) (2) (3) (4)

I don’t recommend leaving the mirror to soak in water for more than a few minutes. Even tiny impurities in water will eventually cause damage to the coatings. Water itself is corrosive to metals.

- Using Acetone or an Alcohol Solvent

If the mirror has some stubborn dirt and grime that isn’t corrosion and the rinse technique outlined still doesn’t work, acetone or alcohol solvent should do the job (keep in mind that most alcohol solvents are partly water and will need to be dried off, whereas acetone evaporates. I prefer acetone). I always make sure to do this in a well-ventilated area and follow all of the safety instructions for the solvent.

I don’t use any petroleum-based organic solvents such as turpentine or mineral spirits, as these can cause problems later on when I go to get a mirror recoated.

If I accidentally leave a huge fingerprint on my mirror while handling it, a quick dab with a lens wipe is fine. But I never rub it across the whole surface.

Corrosion in Mirror Coatings

Mirror coatings can and do eventually corrode unless we observe only under dry conditions and our scope has a closed tube (i.e., a catadioptric like a Schmidt-Cassegrain), or only if we’re very vigilant with cleaning the mirror when dew, pollen, and other contaminants get on it (but not too often either).

Not all corrosion is obvious. A general dullness or dark coloured/missing spots in the coating are the norm, but you can also have tiny pinholes in the coating or notice it is becoming slightly transparent (this can also just be caused by a poor-quality coating to begin with). Many mass-manufactured mirrors have abnormally thin coatings that you might be able to see a flashlight through when one is shone on it; this and similar light corrosion are fine. Small spots of missing coatings or pinholes are also generally not a problem. A damaged coating can usually still perform fine.

The issues to watch out for are animal droppings, bug residue, and pollen. These can not only ruin the coating but can also etch the glass underneath.

It’s hard to balance vigilance with paranoia when it comes to worrying about recoating and cleaning your mirror. Ultimately, the best way to protect your mirror from corrosion is to prevent it from getting very dirty in the first place and be proactive about any serious residue that gets on it.

Generally, if the coating is damaged or failing, I make plans to get the mirror recoated in the near future, unless your mirror is small and cheap enough (such as a 114mm primary mirror or the stock secondary mirrors in many commercial scopes) that replacing it outright is cheaper. In the case of such small mirrors, I just keep using the mirror until it suffers from serious degradation at the eyepiece (which it actually may or may not ever do).

Stripping & Recoating Services & DIY Options

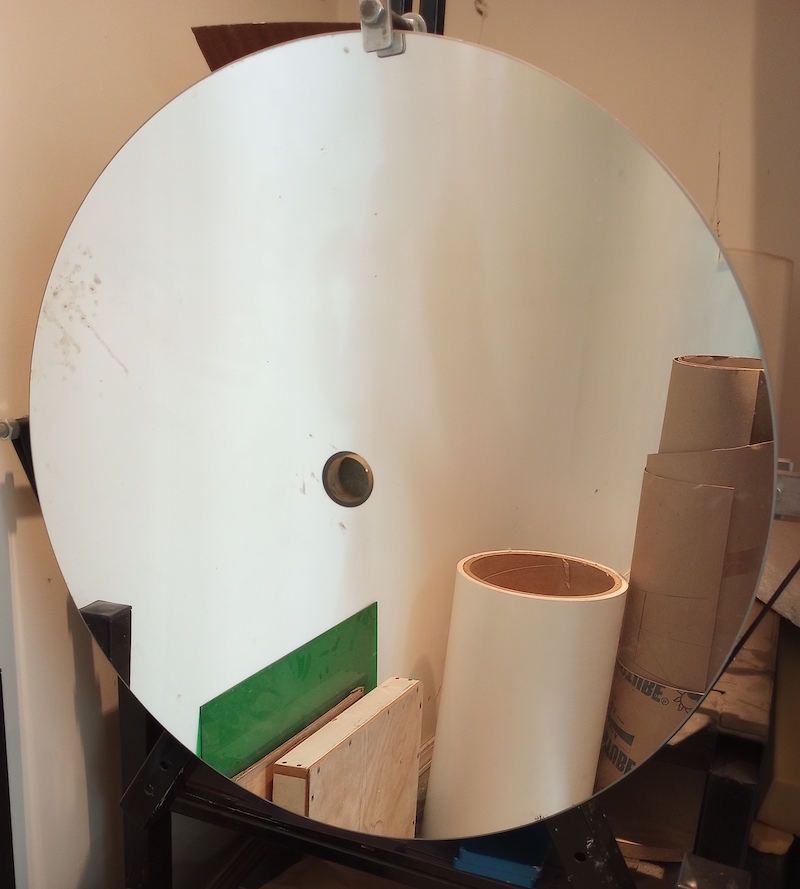

Mirrors have to have their old coating stripped before recoating. This is actually the biggest issue when it comes to sending our mirror to a coater.

Almost any coater can put fresh aluminium or enhanced aluminium on a new, uncoated primary mirror with no problems. However, many coaters—either due to incompetence or attempts to save time—use extremely strong bases like sodium hydroxide to strip and clean optics, which actually causes etching and damage to the glass that ruins the overall quality of the mirror and may cause problems with the coating “sticking” to the mirror.

Unfortunately, coaters that I can trust to strip my mirror correctly are also busier and usually more costly.

As we’ve said, it’s extremely hard to mess up coating an already stripped or fresh mirror. As such, if you’re sending your mirror to a coater you don’t know a tonne about or is known to be bad at stripping coatings, stripping it yourself is fairly innocuous and easy using ferric chloride or “green river” solution.

This does require some precautions and safety equipment but is no more complicated than a high-school chemistry lab. By stripping the mirror yourself, you can be sure that a coater won’t damage your optics.

If you can’t get your mirror recoated (or coated in the first place) in your country due to unavailability or high cost, spray or pour-on silvering is an option. The pour-on silver process is about 150 years old and uses relatively easily available chemicals but can be frustrating to get right and may take several attempts, while spray-silvering is more expensive but more reliable, and kits can be purchased online.

Silvering would not be something I recommend unless your mirror is 16-18” or larger in aperture or there is absolutely no economical way to get your mirror recoated. The fragility and yearly recoating that silvering dictates are really quite a nuisance and not worth the trouble if you can get a good aluminium coating instead.

Further Reading & Videos

- Cleaning your optics – (1) (2) (3) (4)

- Mike Lockwood on coatings

- Mike Lockwood on cleaning

- Gordon Waite – stripping coatings

- General overview of aluminizing by Willie Koorts

- Spray silvering in action (1) (2)

- Oregon Scope Werks on spray silvering